Post by cruororism on Oct 17, 2003 12:42:33 GMT

(1404 - 1440)

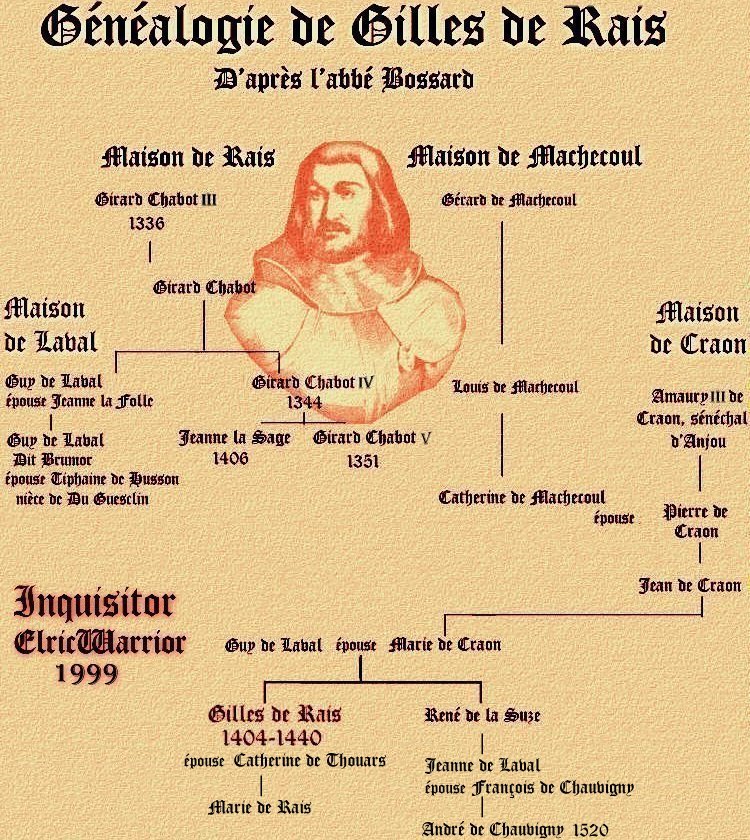

Gilles de Laval, Marechal and Baron de Rais (Rays, Rayx or Retz)

Gilles was born in 1404 in the château of Machécoul. His father died when he was nine, and his mother immediately married again and abandoned her two children to die two years later. Gilles and his brother René must have felt alone in the world.

Their father's will made provision for them to be brought up by a cousin and educated by two priests; instead they were sent to live with their grandfather, Jean de Craon, who had a violent temper, but was too wrapped up in his own affairs to pay attention to his grandsons. His own son had been killed at the battle of Agincourt in 1415, so that Gilles became heir to the entire vast fortune. He was an intelligent child who read Latin fluently and loved music. But he had a taste for the "forbidden" and secretly devoured Suetonius, with his details of the sexual excesses of the Roman emperors. Since Gilles himself was homosexual, these stories must have encouraged the tendency to sexual fantasy, to which he admitted at his trial.

Gilles came from a family of mediæval knights, and was himself trained as a soldier. The Hundred Years War with the English had been going on since 1338, so training in arms was essential for any gentleman.

Five years later, he went to the court of the Dauphin, the uncrowned heir to the throne, and made a considerable impression with his good looks and fine breeding.

He spent his time and money in collecting a fine library, including a copy of Saint Agustine's City of God; but above all he devoted himself to making the religious services held in the chapels of his castles as sumptuous and magnificent as possible. He expended such colossal amounts of money on these spectacular services that even his great wealth was diminished. At the height of his power, Gilles de Rais was the richest noble in Europe, and in 1420 his fortune increased by his marriage to an extremely wealthy heiress, Catherine de Thouars.

In 1429 he was at Chinon when a seventeen-year-old peasant girl named Jeanne, from the village of Domremy, demanded to see the Dauphin, and told him that she had been sent to defeat the English, who were now laying siege to Orléans. The Dauphin thought she was mad, but decided it was worth a try. He ordered Gilles to accompany "the Maid" (la pucelle) to Orléans, perhaps because he had noticed that Gilles was fascinated by the girl's boyish figure and peasant vitality.

Gilles fought by her side when she raised the siege of Orléans, and again at Patay, when she once more defeated the English. At twenty-four, Gilles was a national hero. When the Dauphin decided it was time for the crowning, Gilles was awarded the honor to collect the holy oil with which the king was to be anointed. After the coronation, Gilles was appointed Marshall of France and allowed to include the fleur de Iys in his coat of arms. But after her military triumphs, jealous ministers soon undermined Joan of Arc’s career, and the king was too weak and self-indulgent to withstand the pressure. In the following year she was captured by the English, and burned at Rouen in 1431 with the Church and most of the french noblemen consent; she was only nineteen. (Jeanne who has been made a saint since is one of the great figure of France history and a paradox, she saved thousands of people and pushed the english back to their filthy Channel but she was treated with the most cruelty by the very one who profited from her; she was guided by God’s voice but was called a witch and burned…).

Gilles still had one more martial exploit to come--the deliverance of Lagny from the English. After the coronation of Charles VII, he retired to his estates, at Machecoul, Malemort, La Suze, Champtoce and Tiffauges. After the years of glory, he seems to have found life unbearably dull. And during the course of the following year, according to his later confession, he committed his first sex murder, that of a boy. His grandfather seems to have suspected what had happened; he willed his sword and cuirass to the younger brother René. The grandfather died in the following year, and Gilles was suddenly able to do what he liked.

One of these was a youth called Poitou; he was brought to the château and raped, after which Gilles prepared to cut his throat. At this point, Gilles de Sille pointed out that Poitou was such a handsome boy that he would make an admirable page. So Poitou was allowed to live, and to become one of Gilles' most trusted retainers.

Gilles' attacks of sadism seem to have descended on him like an epileptic fit, and turned him into a kind of maniac. A boy would be lured to the castle on some pretext, and once inside Gilles' chamber, was hung from the ceiling on a rope or chain. But before he had lost consciousness, he was taken down and reassured that Gilles meant him no harm. Then he would be stripped and raped, after which Gilles, or one of his cronies, would cut this throat or decapitate him--they had a special sword called a braquemard for removing the head.

But Gilles was still not sated; he would continue to sexually abuse the dead body, sometimes cutting open the stomach, then squatting in the entrails and masturbating. When he reached a climax he would collapse in a faint, and be carried off to his bed, where he would remain unconscious for hours. His accomplices would meanwhile dismember and burn the body. On some occasions, he later confessed, two children were procured, and each obliged to watch the other being raped and tortured.

Gilles was not merely sexually deranged; he was also a reckless spendthrift. He surrounded himself with a retinue of two hundred knights, for whom he provided. He loved to give banquets and fêtes; in 1435, when the city of Orléans celebrated its deliverance by Joan of Arc, Gilles presented a long mystery play about the siege, with enormous sets and a cast of hundreds, playing, of course, the leading role himself. He also provided food and wine for the spectators. Like a Roman emperor he must have felt that he was virtually a god.

In a mere three years he had spent what would now be the equivalent of millions of dollars. Back at Machécoul, he had to sell some of his most valuable estates. His brother was so alarmed that he persuaded the king to issue an interdict forbidding any further sales of land. For a man of Gilles' unbridled temperament, this was an intolerable position. He went into a gloomy and self-pitying retirement. And now, suddenly, he saw a possible solution. Ten years later, his coffers empty, he believed black magic the answer to his problems.