|

|

Post by Salem6 on Nov 16, 2003 13:06:23 GMT

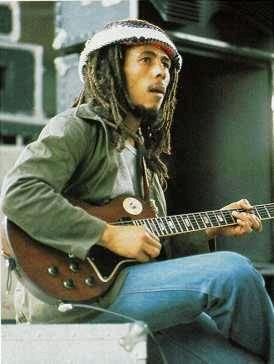

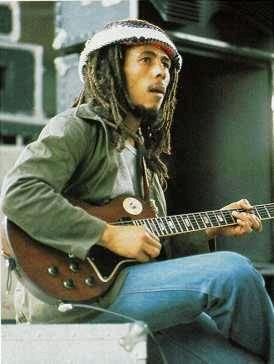

Bob Marley[/u] ![]() home.planet.nl/~kweke000/images/0058.jpg[/img] home.planet.nl/~kweke000/images/0058.jpg[/img]Robert Nesta Marley (February 6, 1945 - May 11, 1981), much better known as Bob Marley, was a guitarist and songwriter from the ghettos of Jamaica. Born in Nine Miles, St. Ann, Jamaica, Marley started in ska and gravitated towards reggae, playing, teaching and singing for a long period in the 1970s and 1980s; Marley is perhaps best-known for work with his reggae group The Wailers, the backbone of which were two other celebrated reggae musicians, Bunny Livingstone and Peter Tosh. Much of his early work was produced with Lee Perry, although the pair split in acrimony over the assignment of recording rights. Marley's work was largely responsible for the mainstream cultural acceptance of reggae music. He signed to Chris Blackwell's Island Records label in 1971, at the time a highly influential and innovative label. Island Records boasted a stable of both successful and diverse artists including, amongst others, such nascent luminaries of the music scene as Genesis, John Martyn and Nick Drake. Much of his work deals with the struggles of the impoverished and/or powerless. Marley died of brain cancer in Miami, Florida on May 11, 1981. He has a son named Ziggy Marley (b. 1968). Nine Mile, situated high in the mountains on the beautiful island of Jamaica, is a small friendly village tucked away in the parish of St. Ann. This quaint hamlet is known as the birthplace of Bob Marley. And it is in this very same place that he was later laid to rest. As many have found, a trip to Nine Mile renews faith in some of the important elements of life. Elements that constantly influenced Bob Marley and are reflected in the lyrics of his songs. If you are ever in Jamaica, we would like to personally invite you to come see, come be... with Bob Marley and his family at Nine Mile. On your journey to Nine Mile you will enjoy breathtaking views while absorbing the natural beauty of the tranquil Jamaican countryside. Look out for the more than 200 species of flowering plants and indigenous trees. Nine Mile is owned and operated by Bob's family. It is not unusual to find his mother, affectionately called Mother B, personally greeting visitors, sometimes even being persuaded to relate stories of her sons childhood. And, if not Mother B, there is always Uncle Lloyd who is never too far away or too busy to tell tales of young Nesta. The tour operators' goal is to ensure that all visitors to Nine Mile are well informed of the history of Bob Marley as they partake in the many cultural experiences the village has to offer. The staff is pleasant, accommodating, courteous and friendly. Their goal is to make all visitors feel like friends and family, which is the way Bob would have wanted it. On the tour, you will enjoy the brilliant and evocative music Bob Marley gave the world. An authentic Rastafarian guide will share with you the natural world of Bob Marley's birthplace, a meditative getaway from the grind of his strenuous career. The tour also touches on the childhood house, the natural kitchen, the "Mt. Zion Rock" (Bob's meditation spot), the "Rock Pillow" (made famous in the song "Talking Blues"). The guide will also share with you information on Marley's later years and on his move and subsequent life in Kingston. The highlight of the tour is walking through the beautiful mausoleum, Bob's final resting place. You will be moved by the calm as you step into the beautiful mausoleum where Marley is laid to rest. Our Nine Mile tour will introduce you to a community that helped influence one of the greatest musicians of this century. It will leave you with a better understanding of a young man, whose vision helped change the thoughts of people worldwide. No small achievement for a man who often spoke of his respect for the simple rural life. Respect that helped guide his life. Respect instilled during his youthful days in the small mountain village locals still call Nine Mile.

|

|

|

|

Post by Salem6 on Nov 16, 2003 13:09:21 GMT

Trenchtown was a housing scheme, built after the 1951 hurricane had destroyed the area's squatter camps. These camps, which had gradually grown up around west Kingston, had been built around the former Kingston refuse dump, where the country folk and displaced city dwellers would scavenge for whatever they could find. (In the days of the 'plantocracy business', the area had been a sugar plantation, owned by the Lindos, one of the twenty-one families that are said to rule Jamaica.)  In 1957, Bob's mother Cedella moved him from Nine Miles to live in Kingston. Like other city-dwellers, Cedella came from the quiet rural surroundings to the Jamaican capital in search of work and excitement. City life offered little respite as poverty and violence plagued Trench Town while the chances of finding jobs were as poor as the living conditions. However, Trenchtown was considered desirable accommodation for the slum and shanty-town dwellers who lived there. The 'government yards' comprised solidly constructed one- or two-story concrete units, built around a central courtyard which contained communal cooking facilities and a stand-pipe for water. Few were so ungrateful as to complain that Jamaica's colonial masters had seen fit to build Trench Town without any form of sewage system. Trenchtown: Spiritual Powerpoint for the Rastafarians Even before the 1951 hurricane had mashed down the zinc-and-packing-case residences of the shanty town, the region was already considered as an area for outcasts. In particular, Trenchtown had now become the main home in Kingston for the strange tribe of men known as Rastafarians, who had set up an encampment down by the Dungle in the early years of World War II. Garlanded in acres of matted, plaited hair, these primal figures, permanently surrounded by the funky aroma of marijuana, could appear as archetypal as a West African baobab tree. It all depended on your point of view and upbringing. Mortimer Planner, for example, considered sufficiently elevated in the Rastafarian brethren to meet His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I, had first moved to the area in 1939. A very simple reason, he said, had drawn him there - the energy emanating from this part of Kingston: "Trenchtown is a spiritual powerpoint." Yet others in the area were not at all happy about the presence of these men with their curious belief that Haile Selassie was God. Why would a young woman called Rita Anderson, a worshipful member of the Church of God, go out of her way to avoid them? Her parents had told her the truth: that Rastafarians lived in the drainage gullies and carried parts of people they had murdered in their bags. No doubt it was such thinking that resulted in the sporadic round-ups of Rastas by the police, who would shove them into their trucks and cut off their locks. As yet, young Nesta Robert Marley knew almost nothing about the Rastas' religion. He was simply getting through his schooldays, perhaps in a more perfunctory manner than his mother realised. Later he would come to realise that his secondary education had been almost non-existent. With no permanent male role model to act as a guide, the transition from childhood to adolescence was even more awkward for Nesta than for most teenagers. In the late 1950s there was a growing undercurrent of opportunism in Jamaica: people were redefining themselves, working out who they were with a new confidence. The guilty, repressive hold of the British colonialists was becoming increasingly uncertain; already there were whispers of independence being granted to the island. A new era was beginning. The cauldron of Trenchtown epitomised one of the great cultural truths about Jamaica - and other impoverished Third World countries: how those who have nothing , and therefore nothing to lose, are not afraid to express their talents. These people seem to have a pride and confidence in their talents - a pride and confidence that western educational and employment systems seem to conspire against. The pace of life in Jamaica also seems to be more in keeping with the rhythms of nature: rising with the sun, people are active from early morning until the sun goes down. Such a harnessing of man's soul to the day's natural process seems to allow the creative forces a greater freedom to emerge. So it was for Nesta Robert Marley. In the cool of first daylight or long after sunset he could be found, with or without his spar Bunny, strumming his sardine-can guitar and trying out melodies and harmonies - his only solace apart from football. For often Nesta would feel alienated in the city. Considered a white boy, his complexion would often bring out the worst in people: after all, why was this boy from 'country' living down in the ghetto and not uptown with all the other lightskin people? Being tested so consistently can virtually destroy someone; or, on the other hand, it can resolutely build their character. Such daily bullying ultimately created the iron will and overpowering self-confidence in Nesta. In 1960 Bob began to take part in the evening music sessions held by Joe Higgs in his Third Street yard. One of the area's most famous residents and a musically prominent Rasta, Higgs was subjected to police brutality during the political riots in Trench Town in May 1959. This experience only strengthened him in his resolve; Higgs used the music clinics to motivate the youth. Higgs was as conscious in his actions as in his lyrics; these included publicly espousing the unmentionable, radical subject of Rastafari, which was growing by quantum leaps among the ghetto sufferahs. Another of the male role models who appeared consistently through the course of Nesta's life, Joe Higgs assiduously coached the fifteen-year-old and his spar Bunny in the art of harmonising: he would advise Bob to sing all the time, to strengthen his voice. At one of Higgs' music sessions Bob and Bunny met Peter McIntosh, another local youth wanting to mek a try as a vocalist. As well as the ganja that filled a crucial gap in Trenchtown's desperate economy, Tartar would sell dishes like calaloo and dumplings. At times when Nesta was entirely impoverished, it would be at Tartar's that he would find free food. When Nesta made the decision to apply himself to the guitar, Tartar would stay up all night with him, turning the 'leaves' of the Teach Yourself Guitar book that Nesta had bought, as he strummed the chords, peering at the diagrams in the light of a flickering oil lamp. In the mornings their nostrils would be black from the lamp's fumes. Nesta had quit school by the time he was fourteen and for a short time, became an apprentice at a local welder's shop. One day he was working on some steel when a piece of metal flew off and hit him in the eye. With the injury causing him serious pain, he was taken to the hospital to have the metal removed. This rogue sliver of metal had a greater significance. From now on, Nesta told Tartar, there would be no more welding: only the guitar. Nesta convinced his mother he could make a better living by singing. By now Bunny had also made a ghetto guitar, similar to the ones Nesta constructed, from a bamboo staff, electric cable wire and a large sardine can. Then Peter Tosh brought along his battered acoustic guitar to play with them. "1961," says Peter Tosh, "the group came together." Encouraged by Joe Higgs, who also became their coach, they formed a musical unit. They were to be called The Teenagers and would consist of the three youths, as well as a strong local singer called Junior Braithwaite and two girls, Beverley Kelso and Cherry Smith, who sang backing vocals. "It was kinda difficult," said Joe Higgs later, "to get the group precise - and their sound - and to get the harmony structures. It took a couple of years to get that perfect. I wanted each person to be a leader in his own right. I wanted them to be able to wail in their own rights." It was now public knowledge in Trenchtown that Nesta Marley, who was beginning to be known more as Bob, was a musician of some sort. At that time Pauline Morrison was living in the area and attending Kingston Senior School. "We'd come from school and see this guy singing, singing, and we'd always sit around and watch and listen to him. After him finish we clap him, and after we'd go home." As a youth who knew what he wanted in life, Bob was not caught up in the negative existence of the ghetto bad boy. He did not move in those packs of adolescents who tried to imitate the exploits of the American slum gangs, typified in West Side Story, which they would catch at the Carib Cinema, having sneaked in the exit door. Bob certainly wasn't some side-walk bully, although, as Pauline points out, "If a guy come for him, and trouble him, him can defend himself." But even then he operated on several levels. On the one hand, he was affable, open, eager to assist: "He was a very easy-going person. He was never rude or anything. Him never be aggressive. Him was always irie to me, even as a kid coming from school. And although I still get to know him and be around him, him never be rude." At the same time, Bob was also a loner. "It was always the man and his guitar," Pauline observes. "But it was very rare you could just sit with him and be with him. Because he was a very moody person, the way I see him. Him is very moody. If people were sitting together with him, he would suddenly just get up and go somewhere else. Just to be by himself." At the end of the day, Bob knew, there was only one person he could rely on - himself.  |

|

|

|

Post by Salem6 on Nov 16, 2003 13:13:22 GMT

Island Records: The Early YearsIn 1959 Chris Blackwell had founded Island Records (so named in tribute to Alec Waugh's 1956 novel, Island in the Sun) in Jamaica, producing his records himself. In 1962 he had decided to move to London, having made licensing agreements with the leading Jamaican producers. Blackwell's releases were aimed at Britain's Jamaican immigrant community: ironically, one of the first records he put out was a tune from Leslie Kong, "Judge Not" by Robert Marley: the surname was misspelled as 'Morley' on the British release. Unlike most white Jamaicans, Chris Blackwell had discovered the truth about the love in the heart of Rastafari; as a teenager in Jamaica he had been on a boat that ran aground in shallow waters; after a long and exhausting swim to the shore, he collapsed on a beach where he was picked up and carried to a Rastafarian encampment; its inhabitants cared for his wounds, and fed him with both ital food and rhetoric from the Rastafarian philosophy. The experience left a lasting impression on Blackwell. Further, the following year when he was running a motor scooter rental business in Kingston, he noticed that Rastas were the only ones who puttered by regularly to pay up. So when he entered the Jamaican record business in 1959, he made a point of investigating the Rastas' ideological and social influences on ska, rock steady and reggae, believing the heroic, principled passivity of the sect to be the source of many of the music's more appealing permutations. In 1964 Millie Small, an act he was managing, had a huge worldwide hit with 'My Boy Lollipop'. After that Chris Blackwell was drawn into the world of pop and rock: he managed The Spencer Davis Group, which featured Steve Winwood, and launched Island as a rock label on the back of Winwood's group Traffic. Soon Island became the most sought-after label for groups specialising in the 'underground' rock of the late 1960s. Bob Marley signs with Island In 1971, at a time when Blackwell was trying to find a way to take reggae into the rock album market, Bob Marley walked into his office. "He came in right at the time when there was this idea in my head that a rebel-type character could really emerge," Blackwell said. "And that I could break such an artist. I was dealing with rock music, which was really rebel music. I felt that would really be the way to break Jamaican music. But you needed somebody who could be that image. When Bob walked in, he really was that image..." Although Blackwell had released Marley's first single, he had hardly kept track of his career. All he knew was that he had been warned about The Wailers, that these guys were "trouble". "But in my experience," Blackwell said, "when people were described like that, it usually means that they know what they want." Blackwell cut a deal with the group who came to him as Bob Marley and The Wailers, as Bob had been billed on 'Reggae on Broadway'. He would give them £4,000 to return to Jamaica and make an LP. When he received the final tapes they would get another £4,000. He also agreed to give to the Tuff Gong label the rights to Wailers material in the Caribbean, which was to provide a useful source of cash in the coming years. (A deal also had to be struck with Danny Sims: for another £4,000 Blackwell bought Bob out of his contract with CBS.) "Everybody told me I was mad: they said I'd never see the money again," Blackwell says. He ignored these naysayers, instead giving advice as to how the three singers should pursue their career. The idea of a vocal trio with backing musicians was dated, he told them: they should take their favourite musicians and forge themselves into a tight road band, capable of touring and presenting several layers of identity in addition to Bob Marley's. On their return to Jamaica, the group immediately went into Kingston's Harry J's studio. By the end of the year, after further sessions at Dynamic and Randy's studios, the album, which was to be called Catch a Fire, was completed. Chris Blackwell set about marketing the record. ![]() www.bobmarley.com/life/island/catchafire.jpeg www.bobmarley.com/life/island/catchafire.jpeg [/IMG] |

|

|

|

Post by Salem6 on Nov 16, 2003 13:14:44 GMT

Roots, Rock, Reggae The decision was made that Catch A Fire should be the first reggae album sold as though it was a rock act. In line with this, rock guitar and keyboards were also added to the LP at Island's Basing Street studio in London's Notting Hill. Then the cover was worked on, an outsize cardboard replica of a Zippo cigarette lighter. It hinged upwards and the record was removed from the top of the sleeve; in fact, it often stuck within the packaging, but the desired effect was created all the same. Danny Sims, eager to sell singles via American radio air-play, had had no time whatsoever for Rastafari subject matter. Chris Blackwell, on the other hand, positively welcomed it. As well as feeling sympathetic to the philosophy of the religion, he understood its strength as a marketing tool. The British music press had always been more important in selling albums in the United Kingdom than the limited radio air-play that was then available. "So what Bob Marley believed in and how he lived his life was something that had tremendous appeal for the media," Blackwell said. "The press had been dealing with the greatest time in the emergence of rock 'n' roll and it was starting to quiet down. Now here was this Third World superstar who had a different point of view, an individual against the system, who also had an incredible look: this was the first time you had seen anyone looking like that, other than Jimi Hendrix. And Bob had that power about him and incredible lyrics," he continued. Catch A Fire was released to critical acclaim and was followed by Burnin', the last album the Wailers' original trio - Bob, Bunny, and Peter would record together. With Island, the Wailers enjoyed International stardom, and the teachings of Rastafari reaching every corner of the globe. Bob Marley performed around the world. From Africa to New Zealand to Japan, Marley travelled extensively to spread his musical message. He performed on the smallest of stages to the largest stadiums, attracting 100,000 in Italy in 1980. This section explores eight significant shows and tours, with rare photographs from Adrian Boot and first-person accounts. The four-night, sold-out stand at London's hip Speakeasy club offers a humble but powerful Bob Marley on stage. This string of concerts offers a glimpse at his first British tour for Island in the Spring of 1973. It followed the release of Catch A Fire, the Wailers' Island debut.  Bob Marley and the Wailers' live radio broadcast at KSAN in Sausalito, CA vividly captured the moment when reggae was poised to enter the mainstream of popular music. The mix of songs from Catch A Fire and Burnin' represent the only live recordings from the Wailers' first American tour.  The July 1975 London Lyceum shows, recorded for the album Live! Bob Marley and the Wailers, reflect Marley's fiery delivery and powerful presence. These extraordinary concerts are described with songs lists from the Live album as well as eyewitness accounts from Dennis Morris and Mick Cater of the performances. ![]() www.bobmarley.com/life/live/frontpage/lyceum.head.gif[/IMG] www.bobmarley.com/life/live/frontpage/lyceum.head.gif[/IMG] No more than 48 hours after a brutal shooting attempt on his life, Bob Marley took the stage at National Heroes Park on December 5, 1976 for the Smile Jamaica Concert. This section describes the foreboding signs and events leading up to the assassination attempt, Marley's decision to perform, and the harrowing drive from Strawberry Hill to the venue. ![]() www.bobmarley.com/life/live/frontpage/smile.head.gif[/IMG] www.bobmarley.com/life/live/frontpage/smile.head.gif[/IMG] The Exodus tour of 1977 reveals the fervor of Marley's live performance and his open defiance of those who would silence him. I-Three Judy Mowatt describes the concerts as "powerful and spiritual...There was a power that pulled you there." ![]() www.bobmarley.com/life/live/frontpage/exodus.head.jpeg[/IMG] www.bobmarley.com/life/live/frontpage/exodus.head.jpeg[/IMG] The April 1978 concert in Kingston marked Marley's triumphant return from exile and the stunning on-stage handshake between Prime Minister Michael Manley and opposition leader Edward Seaga. Their political rivalry had spawned ruthless teams of ghetto gunmen and an outbreak of murder on the island. ![]() www.bobmarley.com/life/live/frontpage/onelove.head.gif[/IMG] www.bobmarley.com/life/live/frontpage/onelove.head.gif[/IMG] Bob Marley promised the organizers of Reggae Sunsplash that he would headline the show at Montego Bay. His first show in Jamaica since the One Love Peace Concert, Marley energized the crowd with songs from the forthcoming Survival LP. ![]() www.bobmarley.com/life/live/frontpage/sunsplash2.head.jpeg[/IMG] www.bobmarley.com/life/live/frontpage/sunsplash2.head.jpeg[/IMG] Bob Marley and the Wailers' first performance in Zimbabwe was marred by tear gas and chaos, yet Marley returned to the stage to perform "Zimbabwe" and prevailed the next day, as over 100,000 people gathered for the second show on April 19, 1980. ![]() www.bobmarley.com/life/live/frontpage/zimbabwe.head.gif[/IMG] www.bobmarley.com/life/live/frontpage/zimbabwe.head.gif[/IMG] |

|

|

|

Post by Salem6 on Nov 16, 2003 13:16:01 GMT

The Caribbean island of Jamaica has had a far greater impact on the rest of the world than one would expect from a country with a population of under three million.

In the seventeenth century, for example, Jamaica was the world centre of piracy. From its capital of Port Royal, buccaneers led by Captain Henry Morgan plundered the Spanish Main, bringing such riches to the island that it became as wealthy as any of Europe's leading trading centres. In 1692, four years after Morgan's death, Port Royal disappeared into the Caribbean in an earthquake. Such a karmic sense of poetry is Jamaica.

A Rebellious Spirit

A piratic, rebellious spirit has been central to the attitude of Jamaicans ever since. This is clear in the lives of Nanny, the woman who led a successful slave revolt against the English redcoats in 1738; of Marcus Garvey, who became the first prophet of black self determination in the 1920s, founding the Black Star shipping line, intended to transport descendants of slaves back to Africa; and of Bob Marley, the Third World's first superstar, with his musical gospel of love and global unity.

Jamaica was known by its original settlers, the Arawak Indians, as the Island of Springs. And it is in the high country that Jamaica's unconscious resides: the primal Blue Mountains and hills are the repository of most of Jamaica's legends, a dream-like landscape that provides ample material for an arcane mythology.

It was here, to the safety of thse impenetrable hills, that bands of former slaves fled, after they were freed and armed by the Spanish to fight the English when they seized the island in 1655. The Maroons, as they became known, founded a community and underground state that would fight a guerrilla war against the English settlers on and off for nearly eighty years.

In this excerpt from Catch A Fire, Timothy White explores the political machinations behind the assassination attempt days before the PNP-sponsored "Smile Jamaica" concert in December 1978.

On the afternoon that Neville Garrick dropped off the revised and final artwork for Confrontation at the Rockefeller Center offices of Atlantic, he returned to Room 722 at the Howard Johnson's Inn at 51st Street and Eighth Avenue to meet with a reggae associate. During the meeting he was shown a copy of a confidential CIA/State Department telegram, declassified on March 14, 1983, as per a request made under the U.S. Freedom of Information Act.

Back in December 1976, the telegram had moved on secure government wires from the American embassy in Kingston to the office of the secretary of state in Washington, as well as to American embassies in the Bahamas, Barbados and other Caribbean locations. The communique's tag line was:

SUBJECT: REGGAE STAR SHOT; MOTIVE PROBABLY POLITICAL.

Reading the four-paragraph wire about the assassination attempt, Garrick was flabbergasted by the implicit message that Marley had been wholly accepted in the intelligence community as a PNP pawn, his usefulness certified regardless of his fate:

1. VIOLENCE IN JAMAICA GAINED FRESH PROMINENCE ON FRIDAY, DECEMBER 3, WHEN BOB MARLEY, POPULAR JAMAICAN REGGAE STAR, WAS SHOT AND WOUNDED.

THE INCIDENT, IN WHICH THREE ASSOCIATES OF MARLEY'S WERE ALSO WOUNDED, OCCURRED AT THE POP STAR'S HOME NEAR THE COMPOUND WHICH HOUSES THE RESIDENCES OF THE GOVERNOR GENERAL AND THE PRIME MINISTER. THE ASSAILANTS HAVE NOT YET BEEN IDENTIFIED, BUT CLEARLY HIT MARLEY AND HIS ASSOCIATES IN A PRE- MEDITATED ATTACK.

2. THE MARLEY SHOOTING HAS CAPTURED EVEN MORE ATTENTION THAN THE REGGAE ARTIST'S POPULARITY MIGHT SUG- GEST WOULD HAVE BEEN THE CASE. IMMEDIATELY BEFORE THE SHOOTING, MARLEY AND MEMBERS OF HIS GROUP HAD BEEN REHEARSING FOR A FREE, PUBLIC CONCERT SCHEDULED FOR A PARK IN DOWNTOWN KINGSTON ON SUNDAY, DECEMBER 5.

THE CONCERT, SPONSORED BY THE CULTURAL SECTION OF THE PRIME MINISTER'S OFFICE, WAS HELD DESPITE THE INCIDENT, WITH MARLEY PARTICIPATING-THOUGH FIVE HOURS LATE.

3. THE CONCERT WAS PART OF PEOPLE'S NATIONAL PARTY (PNP) ELECTION CAMPAIGN, AND WAS SCHEDULED TO COINCIDE WITH THE JAMAICA LABOUR PARTY'S (JLP) RELEASE OF ITS LONG-AWAITED MANIFESTO-TO THE DETRIMENT OF NEWS TIME AND PUBLIC ATTENTION FOR THE LATTER.

4. RUMORS ABOUND AS TO THE MOTIVATION FOR THE SHOOTING. SOME SEE THE INCIDENT AS AN ATTEMPT BY JLP GUNMEN TO HALT THE CONCERT WHICH WOULD FEATURE THE "POLITICALLY PROGRESSIVE" MUSIC OF MARLEY AND OTHER REGGAE STARS.

OTHERS SEE IT AS A DEEP-LAID PLOT TO CREATE A PROGRESSIVE, YOUTHFUL JAMAICAN MARTYR-TO THE BENEFIT OF THE PNP . . . .

"It's alla lie, a blood-clot lie!" shouted Garrick, breaking off his reading in the midst of the fourth paragraph. "None-a this whole report is true. The concert was never political, it was never part of the PNP campaign!"

And then he paused as the realities woven into the communique's detached prose sank in. Despite the murderous antipathies arising from the Caymanas racetrack scam, Bob's presence at the Smile Jamaica concert was perceived primarily as a political statement. Plainly, the communique's text reflected the particulars as the prime minister's office had presented them to the political community inside and outside of Jamaica.

Moreover, the timing of the Smile Jamaica concert had clearly been planned to intensify its political detriment to the JLP. Lastly, the rumors described in the wire's last paragraph were obviously those being circulated through diplomatic channels by mouthpieces for the PNP and the JLP. The conclusion was inescapable: whether Bob performed, perished, or both, the PNP had set him up from the start as a political target.

|

|

|

|

Post by Salem6 on Nov 16, 2003 13:17:51 GMT

When Bob was preparing for a tour, he and his football cronies would follow a strict regime of physical exercise. Rising at 4:30 or 5:00 a.m., he would rendezvous with Skill Cole, who lived in Bull Bay with Judy Mowatt. Then the two of them would link up with Bunny Wailer, at whose place Neville Garrick was likely to have passed the night. There were two possible runs: the mile and a half along road and track to Cane river, where they would wash their locks in the waterfall, or a hard sand run along the beach to Rock, about a mile or so from Bunny's house. If they bought fresh fish from the fishermen who were just coming in with their catches, they would go by Bunny's and fry up the doctor or parrot fish or snapper. If they drove back into Kingston straight away, they would probably stop off at Hope Gardens. Here a woman kept a dozen or so cows, and they would buy fresh, warm milk from her. Back at 56 Hope Road they would make green banana porridge. Skill Cole and Gillie, meanwhile, might get into one of their juice-blending competitions, both being connoisseurs. The Permanent Hustle By ten in the morning the permanent hustle that was rarely absent from the yard would be underway. The Tuff Gong record store would have opened and ghetto rankin's and junior rankin's would be coming up to check Bob or to hustle him for money, or just to cool out: 56 Hope Road was about the only uptown place that a ghetto youth could hang in without experiencing the wrath of the police. During the time of the Peace Concert even Michael Manley passed by to idle away an hour or so. Bob was also extremely welcoming to the 'mad' people - a feature of Jamaican life - who would peer through the white fence, pouring out their stream-of-consciousness rants. "It a mad man," Bob would say, always eager to hear an extreme point of view, "send him in for a reasoning." ![]() www.bobmarley.com/life/56hope/bobstrip2.jpeg[/IMG] www.bobmarley.com/life/56hope/bobstrip2.jpeg[/IMG]Bob used to like holding court in the shades of the awning over the front steps. Serious football, meanwhile, would be in progress on the grass covered front yard. Sometimes a man would come up with large quantities of fish or fruit for Bob. If there was enough fish to go round, they corrugated zinc, and light a fire underneath. Rankin' Gunmen As the voice of the ghetto, Bob could not help attracting gangsters and gunmen, who have always been fond of mingling with entertainers. Alan Cole's position as a sports superstar held a similar appeal. Those around Bob believe he also liked mixing with notorious characters. But Bob could be ruthlessly tough himself: on one occasion he was seen beating a man after he had been caught stealing money from a visitor. Money was always an important issue. On Fridays, in particular, there would be long lines of people waiting for Bob's charity, each with a story to bend his ear. When the school term was about to start, 56 Hope Road yard would be packed with mothers, pleading with Bob for money to buy school uniforms. Sometimes he would distribute between $20,000 and $40,000 at these sessions. Screwface No After the Peace Concert many of the gunmen felt such a debt of gratitude to Bob that they were even more in evidence at 56 Hope Road, to the point where their presence became a problem, even sometimes a threat. Who could tell what nefarious deals were taking place away in some corner under the shade of a mango tree? "But as a Rasta you can't dismiss people," pointed out Neville Garrick. "Him only shield him could wear was him noted screwface: the screwface alone would turn people away. But then Bob love people and always want to help them. Him can empathise with everything. Bob don't have no easier life than any of them. Him kinda raised on the streets." "He grew up with a lot of these guys," said Junior Marvin, "and he wanted to straighten out a lot of them. He was trying to help them. He was trying to say, 'Look you don't really need violence; if you've got that kind of power, you don't have to use it: you can divert it into another kind of positive energy.'" ![]() www.bobmarley.com/life/56hope/bobstrip.jpeg[/IMG] www.bobmarley.com/life/56hope/bobstrip.jpeg[/IMG]In the evenings, however, a different life would go on. Round the back of the house, Bob would sit with his close brethren. Strumming his guitar, he would pick away at new or sometimes old songs. At these, the finest times, a peace of almost visible proportions would descend. And, protected by Jah, Bob would be in touch with the deepest source of his creativity. Today, 56 Hope Road still remains an active place for reasoning, now home to the Bob Marley Foundation and Museum. |

|

|

|

Post by Salem6 on Nov 16, 2003 13:20:45 GMT

Passing onA Nagging Injury While playing soccer in Paris with a top French team in May 1977, during the European leg of the Exodus tour, he had injured his right toe again during a bad tackle. The toenail was torn off. Again, it seemed minor at first. This time however, the lesion did not heal. But he pressed on through the Scandinavian concert dates. Worries among Bob's inner circlew of Dreads concerning his physical well-being quietly mounted. On July 7, 1977 Denise Mills, executive assistant to Chris Blackwell and the chief Island Records official accompanying the Exodus tour, took a limping Bob Marley to see a physician, who told Bob his wound looked disturbingly bad. It got so bad, in fact, that London doctors ultimately prescribed amputation of the right toe. Bob refused, in acccordance with Rasta proscription against such surgery. He was flown to Miami from London where Dr. William Bacon, a black orthopedic surgeon, performed a skin graft on the toe. Bacon called the operation "a success". On Sunday morning, September 21, 1980, Bob and Skilly had gone jogging in Central Park to get Bob "energized," as Cole put it. The night after the second show of his Madison Square Garden concert series with the Commodores, Bob had awoken in a daze; he had trouble remembering the show, even the fact that he had almost passed out during the performance. As Bob was running around the pond near Central Park South that Sunday morning, he felt his body freezing up on him. He turned to tell Skilly something was wrong, but his neck suddenly became rigid; he couldn't speak. He was unable to move his head as he fell forward. Skilly got Bob back to their hotel, the Essex House. Bob gradually revived, but he was severely shaken. Nevertheless, the decision was made to go on to Pittsburgh the following day for a Tuesday night show. His performance at the Stanley Theater on Tuesday, September 23, 1980 was to be his last. Terminal CancerBob was secretly admitted to Manhattan's Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and underwent radium treatments that caused the locks around his forehead and temples to drop off. After two days, word leaked out that he was there. Although he was scheduled to be in the hospital for at least two weeks, when he learned the rumor had been announced on WNEW-FM and published in the New York papers, he immediately checked out, ignoring doctors' warnings that without proper, intensive treatment, he might not live another ten weeks. Based on tests taken thus far, cancer tissue was detected in his liver, lungs and brain, and there was evidence that the disease was spreading to other vital organs. A Jamaican physician, Dr. Carl Fraser, a favorite of Twelve Tribes Rastas, who called him "Pee Wee," suggested that Bob seek treatment from Dr. Josef Issels, a seventy-two-year-old German doctor who specialized in helping those with so-called hopless, untreatable or terminal cancer. By November, Bob was scheduled to move to Issels' clinic in Rottach-Egern, a tiny town in Bavaria's foothills near the Austrian border. On February 6, 1981, Junior Marvin, Seeco Patterson and Tyrone Downie hosted a little birthday party for Bob in his quarters at the Ringberg Clinic. They sat together watching a TV show about the World Cup that featured highlights of Pele's performances over the years in the championship matches. Bob seemed strong, alert and in good spirits. But as spring arrived in the Tegernsee Valley, the day finally came when Issels announced he could do no more. Bob was flown back to Miami. In a phone call to his attorney, David Steinberg, he made him promise that he would not rest until the publishing rights to all of Bob's songs were retrieved and turned over to his family. "Maddah, don' cry," he said afterward to Ciddy as she stood at his bedside, clutching his hand, "I'll be all right. I'm gwan ta prepare a place." He died just before noon on May 11, 1981, only forty hours after he left Germany. At that moment, back in Kingston, Judy Mowatt was sitting on the veranda of her home on the outskirts of the Liguanea section of Kingston when a great burst of thunder shook the heavens and a bolt of lightning hurtled through her open window, glancing off the framed photograph of Bob on her mantelpiece. Frightened, her children began to cry; after calming them, Judy turned on the radio and heard the JBC bulletin that Bob was gone. "Death is swallowed up in victory... O Death. Where is thy sting? O Grave, where is thy Victory?" -I Corinthians The people of Jamaica came from all over the island to attend Marley's funeral. His funeral service was held in Kingston's National Heroes Arena. He had been given radiation treatment to fight the cancer invading his body, and as a result, his dreadlocks had fallen out. Rita, his wife, had kept the locks and they were woven into a wig which was placed on his head. Sharing Bob's coffin with him were his Bible and his Gibson guitar. At the state funeral there were readings from the Bible by Jamaica's Governor General, and by Michael Manley, the Leader of the Opposition Party. Edward Seaga, the Prime Minister, eulogized The Honourable Robert Nesta Marley. The Wailers, with the I-Threes backing them up on vocals, performed some of Bob's songs. The Melody Makers, a group consisting of four of Bob and Rita Marley's children, led by their eldest son Ziggy, also performed in his honor. His mother, Mrs. Cedella Booker, sang "Coming In From the Cold", one of the last songs Bob wrote.

|

|

|

|

Post by Salem6 on Nov 1, 2004 9:50:54 GMT

Kate Simon's striking images of the reggae kingpin capture his essence. by Jim Macnie  (Photo: Kate Simon) Bob Marley cackling as his band the Wailers take their reggae grooves through some very funky paces. Bob Marley sleeping, slouched on a couch while songs are sung around him. Bob Marley in a passion dance, rocking his dreads in a sprayed twirl that defines his animated stage presence. Music tells us a lot about a lot about pop heroes, but pictures – or at least the most eloquent pictures – can explain just as much. When you see reggae's most profound symbol rehearsing his group at Copenhagen's Tivoli Gardens amusement park - Tilt-a-Whirls, Ferris Wheels, and rollercoaster in the background – you get a feel for Marley the working musician, not Marley the superstar. Kate Simon's "Rebel Music: Bob Marley and Roots Reggae" is a rich compilation of the photographer's travels with the Jamaican legend during the late '70s, and its visual candor is unusually expressive. Simon, who snapped the Clash's first album cover and documented loads of musicians throughout the years, shot Marley on numerous occasions (there are 400 images in the book, which is a limited edition of 2000 copies, each one numbered and signed). On the stage at London's Lyceum, on the bus during the famed Exodus tour – "Rebel Music" is rich with the intimacy and perspective that comes from a subject yielding to an image-maker. There's a great offhand feel at work - even the pictures of the funeral parade that stretched across Jamaica when the singer died - and it draws you into Marley's intriguing world. Simon, who starts a show of her Jamaican archive at the Govinda Gallery in Washington, D.C. on December 3, began taking pictures of rockers in London during the early '70s. These days she makes portraits of authors, painters, and musicians (her work can be seen at Rockarchive.com ). She spoke to VH1.com about capturing someone's spirit with a photograph. VH1: Why did you start shooting musicians? Kate Simon: I knew I wanted to be a photographer. I went to college in Paris, and hit London afterwards, and liked it as a city. I got a job at the Photographers Gallery, which was fortuitous. Cecil Beaton and David Bailey were around, and they influenced me. I learned how to see as a photographer. It was a good environment. Someone asked me if I'd take a shot of Fairport Convention, and I was off. Music was just a part of the culture back then - it was everywhere. If something happened to a music figure, it was front page news: ROD STEWART BUYS SOME ARGYLE SOCKS! I became a staff photographer at a magazine called Disc, and then moved on to Sounds, NME, and Melody Maker. I basically shot every act that came through London. A small cache of photographers who were my friends would be in the orchestra pit of all those great theatres: Me and my colleagues, a foot a way from James Brown. It was a fantastic time. VH1: Where you the de facto photographer for Marley? KS: No, there were a few of us. I think everyone has a different thing they can get from a subject. VH1: Tell me what you think you personally brought out of him and the band. KS: Well, Bob taught me that it takes two to make a great photograph. He made himself available 100% of the time. Whenever I wanted to take a shot, I knew he'd be cool about it. It's the idea that you can't take someone's photograph, they have to give it to you. With Bob, he walked it like he talked it – he's a lovely person. I can't really say what I got versus what someone else got. I was just trying to do the best I could. Maybe there's something unique that surfaced because I'm one of the only women who photographed him. Maybe he gave me something he didn't give men. VH1: Politics were at the heart of Marley's art. But though he was known as a serious person, the book also positions him as an easy laugher. KS: True. It depends on what each photographer is going for. What I'm going for is nothing short of the truth. I want to get to the essence of who the person is. As you say, on one hand Bob was relaxed and chill, maybe smoking a spliff or hanging out having fun with Gilly, his cook. But you can see that he was dead serious about his music and various subjects – he was very thoughtful and very committed to his faith and to helping other people. VH1: Can you remember your first reaction when you hit Kingston in the mid-70s? I'm talking about the town itself as well as the reggae scene. Must have been quite a spectacle. KS: I went to Jamaica, and I'd never seen any group of people offer such a great profile. It was just screaming to be preserved. There were lots of characters down there - Bunny Wailer for instance. What a great subject, right? The streets were like a dream, a Jamaican Clint Eastwood movie. These people had more style than I'd ever seen in my life. There was just something fantastic about their inherent movement – the way they skanked down the street, the way they put their threads together. And then the cast of characters was wild. You had Lee "Scratch" Perry, Leroy Smart, Dillinger – that guy had more profile than you can imagine. Big Youth – what a face. You'd go to Scratch's studio, Black Ark, and you were always welcome, and he'd have some killer group that he'd be producing and he'd be dancing and smokin'. In 1976 the scene centered around the Sheraton. It would be like what Polo Lounge or the Beverly Hills Hotel was - one hell of a scene. Around this 50-meter swimming pool you'd see John Lydon, Joni Mitchell, Mick Jagger. Everybody made it to that pool. That's where I shot the Kaya cover. VH1: Chris Blackwell says you had a "war correspondent" vibe when you were on the road with the Wailers. KS: When you're shooting something as great as Bob Marley and the Wailers, you know it's an opportunity. You're focused, committed and you'll do anything to get the shot. When I got back from the Exodus tour, I literally couldn't speak for five days – that's true. I think it was a post-traumatic situation. I'm known as a blabbermouth, so that was curious. VH1: [Rock photographer] Henry Diltz says better shots are made if you have a camaraderie with the subject. Do you need to be pals to get the job done? KS: Yes, yes, yes. I'm quite fond of Henry Diltz's photographs, and that seems to be his approach. I'm not someone who went after all these people I shot. The Clash were my friends; that's why I did their album cover. With Marley, we had a rapport, we were simpatico. It made sense that Chris sent me on the road with him. Patti Smith or some of the others I've shot – they're pals and have become part of my tribe. You're trying to get some of the soul and the spirit of the person, and they're not going to give that away to someone who's creeping 'em out. VH1: What are you favorite Marley tunes? KS: Here are some songs that will give people joy. "Jah Lives," on the reissue of Rastaman Vibration. The entire Exodus record - "Guiltiness" is my favorite. "No Woman No Cry" from the Live! album. "Pass It On" from Burnin' Bunny's vocal is so beautiful and there's a great message of brotherhood. I love it when the three of 'em - Bob, Peter Tosh, and Bunny Wailer – were together. Which is why we have to give it up for "One Foundation," Peter Tosh's tune from Burnin'. Someone was telling me about this man: "You've got to photograph him; his speaking voice is fantastic." And sure enough, Tosh was a guy with a great speaking voice - so basso and profound. Lightning would fill the sky and he'd say "Jah Rastafari – you hear that lightning? I made that happen." I like "Reincarnated Souls," "Want More," "Time Will Tell," "Wake Up and Live," and "Comin' in From the Cold." I'm not a music critic, but my absolute favorite Marley tune is "Forever Loving Jah" VH1: Your shots of Marley dancing on stage, twirling his dreads in a spray, really remind me of his performance persona – they're so vivid. KS: This book is commerce, but it's a really a labor of love. I really liked Bob a lot. I never met a photo subject as generous as he was. When I got to the funeral pictures [which close the book] it hit me like a wall, because I hadn't looked at them since I took 'em. The funeral was like a Cecil B. DeMille movie – the whole island came out in love for Bob. There was a four-and-a-half-hour drive, from Kingston to St. Anne, where he was put in a family mausoleum; people were booming Marley music all along the way. I was right in front of the car he was in...I think this will hit everyone: you're going along in the book, and you're involved in the spirit of the Rastafarians, Kingston, the Wailers. And then the funeral is just – WHOMP! You really see how this person, who was imbued with such vitality, had such an impact. He was all about positive energy. On the Exodus tour, whenever he hit "Lively Up Yourself," the audience was his. Rebel Music is $395. It's available from www.genesis-publications.com. www.vh1.com/news/articles/1493060/20041026/marley_bob.jhtml?headlines=true&_requestid=262051 |

|

|

|

Post by Salem6 on Nov 1, 2004 9:51:56 GMT

Bob Marley plays London's Lyceum in 1975.  Marley at the London Lyceum, 1975.  Kate Simon: "Bob's face is so open, his smile is so big, his gaze so sharp the photograph seems to give off light."  Kate Simon's book tells Marley's story in pictures and reminisces.  Kate Simon: "He often seemed to have a kind of melancholy about him. He was serious, pensive."  Randall Grass: "It wasn't a performance, it was more a transcendental experience for him."  Kate Simon: "I always wanted to get as much eye contact with the subject as possible. I look for that."  Bob Marley the night before he opened at London's The Rainbow.  Bob Marley backstage. |

|

|

|

Post by Salem6 on Nov 1, 2004 9:52:42 GMT

Bob Marley: "Record company no realise, this music can unify the whole universe."  While on tour, Bob Marley kept himself informed via the newspaper.  Marley catches up on world events.  Marley would often fly alone, and always took his guitar on the plane with him.  Marley with the injured toe that would later kill him, 1977.  Kate Simon with Bob Marley.  Bob Marley after a performance in Berlin.  Bob at an Ethiopian fund-raising function in London.  Bob Marley enjoys himself with friends.  Spencer Davis: "When he played live, he was totally absorbed in the music." |

|

|

|

Post by Salem6 on Nov 1, 2004 9:53:42 GMT

Bob Marley plays at the Tivoli Gardens.  Marley works out an arrangement with Family Man at the Tivoli Gardens.  Kate Simon says it was difficult to get a live shot of Marley with his eyes open.  Bob Marley live.  Soccer was Bob Marley's second love.  Before shows, Marley would warm up practicing headers.  Bob Marley with his band.  Bob Marley during rehearsals for the One Love Peace Concert in Jamaica.  Marley brings together the Jamaican PM and the leader of the opposition at the One Love Peace Concert.  Bob Marley's funeral, 1980.  Rita Marley and her children at Bob's funeral. |

|

![]() home.planet.nl/~kweke000/images/0058.jpg[/img]

home.planet.nl/~kweke000/images/0058.jpg[/img]